Aaaaaaand, we’re back! New semester, woo woo.

My original plan was to get this over and done way back in January. My thinking was, nobody wants to recall 2020 any more than we absolutely have to, so why not get the requisite “Best Of” list out of the way as soon as possible? It was a good plan, or so I thought, until I remembered just how many films I had yet to see, films which by all accounts I needed to see in order to make any self-respecting Best Of list complete (even if it was just to say, “Yeah I saw it, wasn’t a fan).

This proved a problem, since – like everybody else – I spent most of 2020 at the mercy of staggered VOD releases and a lack of safe cinema viewings. There are movies that show up on this list – Saint Frances, Nomadland – that I literally wasn’t able to see until earlier this year (my first viewing of Saint Frances was literally just a few days ago). Does this mean they should technically count as 2021 films rather than 2020? Honestly, at that point we’re getting into semantics that I couldn’t give less of a damn about. It’s the same sort of thing that happened with Portrait of a Lady on Fire last year; it’s a 2019 movie, and I counted it as a 2019 movie, but because of some staggered release fuckery I wasn’t able to see it in a cinema until February 2020 (I even joked in last year’s rundown that it’s movie so good, I might have to count it again this time).

Fundamentally, it doesn’t matter if these are all 2019 movies, or 2020 movies, or 2021 movies; these are all movies that I loved, which either spoke to me on a deep level or just entertained me really well for about ninety minutes. Semantics be damned; this is the list. And because 2020 seemed like such an onslaught of negativity, I thought it might be nice to go way past the usual 10 and instead settle for 25 of the best offerings of the year. So, woo!

The Assistant

This is kind of a tough one to recommend, as it’s low-key and naturalistic in a way that could be considered a fault. I’ll admit that the first time I saw it, I almost didn’t know what to make of it, and it really had to percolate in my brain before I could get a handle on it. But since this was one of the first movies I saw all year (it was definitely the first one I saw in a theater, back when that was a thing), it’s had a while to percolate in my heat. And I gotta say, the longer it’s been, the more I’ve grown to love it, and at this point I’m holding it up as proof that aspects to a film that usually are considered automatic negatives – a drab color palette, dull lighting, flat camera angles and basic movements – can be used and repurposed into positives. Because this is the type of movie where, if it were made more conventionally, it would not work.

This got some notice at the beginning of the year as Hollywood’s first stab at tackling the whole Harvey Weinstein scandal, a prospect that immediately sets off some pretty strong alarm bells. But The Assistant manages to deftly avoid every potential pitfall of bad taste or faux moralizing, successfully shining a direct spotlight on the broken system that allowed this monstrous predator to flourish unchallenged for so long. And that’s where the focus stays; the system. At no point in this film is the name “Harvey Weinstein” uttered, nor does he ever make a physical appearance, either played by an actor or shown via archive footage of some sort, which I think is an important call. It keeps the focus squarely on what still needs fixing, rather than building up a monster so we can pretend we already solved the problem by bringing him down.

The Kid Detective

My love of the whodunnit genre was probably pretty self-evident from anyone who read my “Knives Out/Irishman” article from a couple of months ago, as are my feelings about whenever film tries to take on the genre; namely, that is is very, very hard to do, and almost never works. A perfect whodunnit should manage to strike a balance between an engaging, thoughtful mystery – one that plays fair with its audience in terms of clues and internal logic – and an interesting main detective who has a character arc of his own. This is, obviously, one hell of a tall order, and it’s all too common for movie mysteries to prioritize one over the other; either you’ll get a film with strong character work but weak mystery plotting (Gosford Park, Lantana) or a film with too much focus on the mystery and not enough focus on characters worth giving a shit about (The Last of Sheila). Part of what made 2019’s Knives Out such a miracle was how deftly it managed to merge these two halves; it had a plot straight out of Agatha Christie at her peak, and characters with honest-to-god arcs.

I was actually reminded a lot of Rian Johnson while watching The Kid Detective, since the closest analogue I can think of to this is Johnson’s first film, the high-school neo-noir Brick. Like that film, The Kid Detective gets a lot of comedic milage out of characters not acting their age; with Brick, the joke was that it was a bunch of high schoolers behaving like they were characters in a smoky pulp thriller, and here, the joke is that it’s an adult man who still acts like he’s a precocious kid detective, a la Encyclopedia Brown. It’s a sad situation for any guy to be in, and the film hits a great tightrope; it takes his grief seriously, and it mines his arrested development for legitimate pathos, but it also recognizes that the idea of a grown-ass man acting like he’s Nancy Drew is really, really funny.

Ordinary Love

I have a theory that movies like this exist solely to blindside cynics. On the surface, there is little to distinguish Ordinary Love from any number of weepy, cloying, serious-faced dramas about old people and cancer, all that fun jazz that awards season falls over themselves to shower with praise. But Ordinary Love is so far removed from the saccharine, Oscarbait-y nonsense it sounds like from its description that it almost isn’t fair. This is an honest-feeling, realistically emotional movie; no room for the Oscars’ faux platitudes here. It’s also one of the increasingly rare instances where Liam Neeson takes a break from punching generic bad guys and goes back to punching our feelings.

Clemency

The first thing you should know about Clemency is that that is a fucking ironic title. There is precious little mercy in the whole film; not for the inmates, not for the wardens, and certainly not for any of their families. It’s a drama about the death row process, and the first thing we see is a botched execution. Everything, from the unnatural color of the fluid, to the blood that pools around the needle’s entry point, to the twitching convulsions of the man strapped to the table, burns itself into our brain. Importantly, it’s a scene that’s hard to watch without ever coming off as exploitative, which is vital to the success of a movie like this. Because it’s not about the executions, not really; Clemency’s main focus is on the people caught in this process, and the psychological damage it has on them. And it’s so effective at this that is bypasses any reservations you might have about its subject matter, instead engaging you in one of the most empathically human stories of the whole year.

Bait

There’s a lot about Bait that might paint it as a spiritual cousin of sorts to the previous year’s The Lighthouse; monochrome cinematography, reduced aspect ratio, unusual audio, and a general tone of ambiguity. That tone of ambiguity actually almost put me off the whole thing, as it took me a good 10 minutes of general confusion before I really started to get a handle on what Bait was going for. Once I did, though, I was hooked like a fish; fitting, considering the film’s seaside setting. This is the best kind of strange movie; it pulls you in with its unconventional presentation, and by the time you get to the end, you realize all those quirks actually served a purpose.

Emma.

The thing about Jane Austen is, there’s the cliched “idea” of what her works amount to – fancy clothes, upper crust British accents, and way too much dancing – verses the rich life that actually exists within her text. I’ve not yet read Emma (though for whatever it’s worth, I did see Clueless way back when), but the quality and depth of the world which this movie creates tells me that they brought the source to life about as well as can be done. This was one of the few films from early 2020 that I did manage to see in theaters, which is great, because this is a big-screen movie through and through. It’s not just the details on all the sets and costumes, but the way the colors just pop off of the screen was something to behold. Bright and sunny movies like this really do put all those dour, smoggy CGI-fests to shame.

Days of the Bagnold Summer

There are few things harder to pull off in storytelling than sincerity that isn’t mawkish or saccharine. In that respect, Days of the Bagnold Summer is a triumph. Like with the best movies of it’s kind, it’s the sort of thing that you can imagine going completely wrong, if the script was a little less on the ball or the director didn’t give a shit, this exact same setup and plot could’ve resulted in something unwatchable. Instead, it all was calibrated to just the right degree. Instead of sickly sweet nonsense, this film is low-key one of the best of the year.

The Vast of Night

A childhood spent watching The Twilight Zone prepared me for this movie, and even so, I wound up more delighted in it than I expected. It’s not just that this film perfectly apes the surface-level aesthetics that defined shows like that; no, what makes The Vast of Night such a fantastic film is it’s deeper understanding of why these kinds of stories fascinate us in the first place. While The Kid Detective might be the better “mystery movie” at least in terms of having a complete mystery at its center, it’s this movie that really manages to capture the addictive nature of these kinds of narratives. Who wouldn’t want to be the one to prove that there really is something out there?

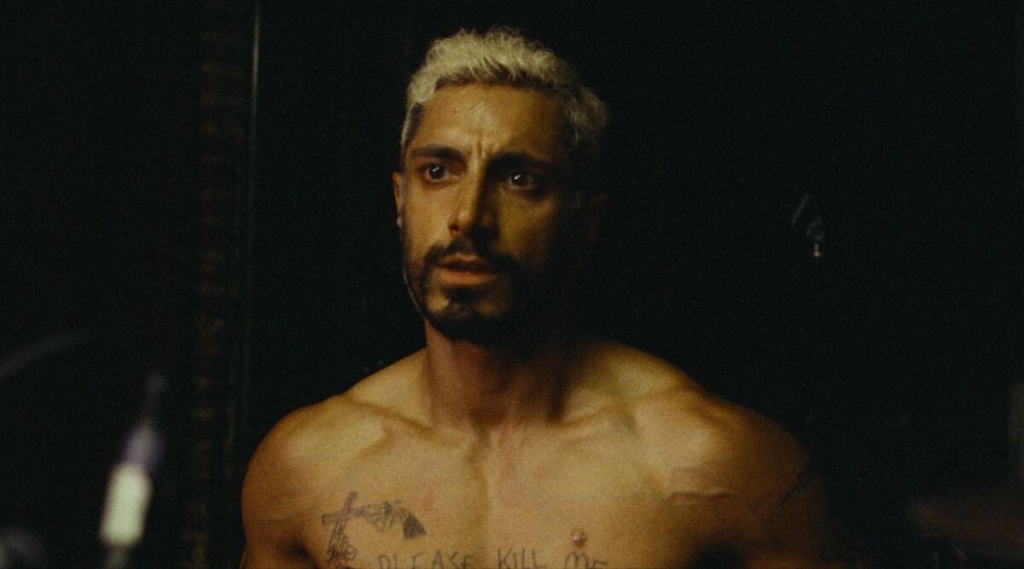

Mogul Mowgli

What we’ve got here is Riz Ahmed (who also co-wrote the film) playing a rapper who’s about to break through with his first big U.S. tour, when he’s suddenly struck down with this degenerative illness, the type that makes it increasingly impossible to lift his limbs without assistance, among other things. With his whole career seemingly on the line, Zed begins to spiral inwardly as well as outwardly, and his mind becomes tormented with violent hallucinations. In a lot of ways, this whole movie comes off as a violent hallucination. It’s filmed excellently, so vibrant and eclectic, and what it comes off as is like the whole movie is one massive freestyle inside this dude’s brain. Like, the movie begins with Riz Ahmed rapping (and holy shit, this dude can rap, to the point where I’m not really a fan of rap, but after this movie, I think I’m a fan of rap), and it’s one of the most propulsively energetic scenes of the whole damn year. But then the movie keeps going with that level of kinetic energy, and it really does feel like the movie itself is keeping the beat going.

System Crasher

What’s with Netflix, dumping all their most interesting movies in a clump where no one will notice them, all while promoting trash like Project Power for weeks on end? I don’t know, and I don’t like it, because this was one of my favorite movies of the year, but despite being readily available on one of the premier streaming services, there’s a good chance that 99% of people with subscriptions don’t know it exists. And they should, because it’s awesome; tackling a subject that could easily descend into clichéd platitudes, what System Crasher does instead is use immersive direction and really raw performances to craft a story for which it understands there are no correct answers. Unlike other, lesser movies about “problem children,” this movie never looks for the easy way out.

Sound of Metal

Riz Ahmed has been on a tear lately; he’s already shown up on this list once already, with Mogul Mowgli. Funnily enough, this actually serves as an interesting spiritual cousin to that film in a lot of ways; in both, Ahmed plays a musician who’s convinced he’s about to make it big, until he’s suddenly struck down with a medical affliction (in Mogul Mowgli it was a variety of ailments; here, it’s just deafness), and the rest of the movie has to do with him coming to terms with his new reality. It’s real, it’s raw, and it’s great because it refuses to either pull any punches, or descend into misery porn, instead balancing out perfectly as a pointed, but empathically human character study.

A White, White Day

This here is a “wavelength movie” if ever there was one; you really need to be able to get on this thing’s register if any of it’s going to work for you. There’s long stretches in this movie where nothing is happening, and we’re just left to absorb the silence and the atmosphere. Early on, there’s a series of static shots of this one, unfinished house, and we see the landscape switch from night to day, night to day, night to day, night to day, and this happens for at least a full minute. Later, the main character, Ingimundur, is driving his truck, when he hits a boulder in the middle of the street. He successfully rolls it to the side of the road, and pushes it over the edge (he’s driving on a mountain). We follow the boulder’s long, tumbling journey down to the bottom, again in a series of completely static shots. To some, this will be elusive, and annoying. To others, it will just be boring. For myself, I saw it in just the right headspace to appreciate something like this, and as such, the overall effect of the film was honestly hypnotic. Something about the combination of long takes, of silent scenery that’s just a little too overexposed, of the general lack of context or the film’s initial refusal to give you a definitive foothold in the story, it all worked for me.

It helps that the story is already inherently interesting to me; it’s another mystery movie, this time having to do with an off-duty police officer who begins to suspect his recently deceased wife of having an affair. But what’s important to understand – and what the film makes clear very early on – is that this is waaaay more a character study than it is a mystery movie, with the film spending much more time on the character’s internal mechanics than his outward actions. Like I said, this is a mystery movie, but the mystery is actually the main character; as played by Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson in what might be the performance of the year, Ingimundur is one of the most captivating screen characters of the past decade, a fascinating mess of compulsion and turmoil that was more than enough to carry me through this potentially off-putting presentation. It’s not always a lot that separates art from pretentious shit, and without that character, and that performance, I’m not sure A White, White Day would’ve found itself on the right side of that divide. But he’s there, and it’s enough.

Fourteen

Who’d have thought, in a year where a new Christopher Nolan movie came out, that this is the most interesting film to use time as a weapon. Fourteen is a movie with a simple premise; it’s basically a portrait of this friendship as it evolves throughout the years. And in execution, that’s exactly what it is, except that it entirely forgoes any sort of signifier for what era of their lives it is, or how much time has passed since the last time we saw them. It will cut from one scene to the next, and anywhere from weeks to months to even years will have passed, and we’re basically left to try and keep up without any hand-holding. And it works, because this is the kind of story that warrants a stream-of-consciousness presentation.

Zombi Child

It’s films like this that reveal the shallow simple-mindedness of both the viewing public for insisting that there’s nothing interesting left to be done with the zombie genre, and the gutless studio system for validating that belief with an endless stream of completely interchangeable zombie movies. I remember when Train to Busan came out, and was heralded as a revolutionary zombie flick. This, at least, one-ups it in that respect, and a couple of others too. In so many ways, this feels like a throwback, like it comes from that strange era of zombie lore that existed before Night of the Living Dead came along and reinvented the whole thing in its image. The primary driving force behind the narrative is voodoo; the film opens in 1962, where a Haitian man collapses in the street and is pronounced dead. We see his corpse lying in the casket, we see them having a funeral for him and everything, so it’s a bit of a surprise when he’s next seen shambling around, wandering the streets of his old haunts apparently as a member of the living dead. From there, the film unfolds with a multi-generational narrative that has to do with the family, heritage, and the echoes of trauma. This isn’t a movie that’s interested in hordes of the undead closing in and eating flesh. Rather, it’s main setpiece sees a lone zombie seeking out his own gravesite.

Rocks

Rocks is a heartwarming movie; better, it’s an actually heartwarming movie, not one of those Hallmark flicks that always seems two seconds away from suffocating you with diabetes for how sugary it is. This movie’s emotional core is honest. And the way it delivers on that emotional core oozes with lived-in naturalism; the whole film is populated by child actors who do that rare thing in movies where they feel like real kids. In fact, the world feels so lived-in, and the characters so complete, that I honestly could’ve spent the whole 90 minutes just watching them go through their lives, and not have any sources of conflict or “plot” ever show up. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a good story, and it doesn’t interrupt anything else or come out of nowhere, or anything like that. But this film was already doing such a good job of immersing me in its world, that I’m convinced it could’ve sustained itself on just that low-key register right to the end.

Nomadland

If there’s a running theme in this rundown, it’s me trying to sell these movies which, on the outside, just seem like the most maudlin, pretentious shit. That’s probably never been more true than with Nomadland, which I’m gonna have serious trouble even describing, let alone making it sound like viable entertainment. Basically, the whole movie is about Frances McDormand as Fern, a woman living in the margins of society. And, that’s basically it. But that’s all this movie needs. This is a genuine masterclass in low-key grandeur, that combination of tactical groundedness and sweeping splendor. God, I have no idea how this director is gonna make a Marvel movie.

The Way Back

I am infinitely more fascinated by artists and creators whose output is hit-or-miss than I am by consistency, no matter how good that consistency tends to be. In so many ways, Ben Affleck is the poster boy for fascinating inconsistency; after being considered little more than a joke for basically the whole of the early 2000s, he managed to achieve a legitimately inspiring comeback by writing and directing (and occasionally starring in) some pretty fantastic films, like Gone Baby Gone, still my favorite of his cinematic output. This new lease on his career was seemingly solidified by him winning the Oscar for Argo…and then he went and played Batman, where probably the nicest thing you could say about it was that he was the best part of a pretty poor bunch of films. Billed as a comeback movie – both for the character Ben Affleck plays, and Affleck himself – The Way Back gains serious depth from just how deep into his own demons the star is willing to mine. There’s an emotional honesty to this movie that just can’t be faked, and the details of Affleck’s character’s alcoholism feel lived-in and genuine. The most impressive thing about the film is that it recognizes that redemption isn’t easy, and the path back to an okay place – not even a good place, just a manageable one – oftentimes feels impossible.

The Climb

The Climb is another interesting, elusive movie. Like Fourteen, it’s a portrait of a friendship’s evolution over the years, and like Fourteen, it presents itself in a very stream-of-consciousness manner. There are time jumps within the scene transitions, and half of the movie is spent with the audience trying to get back up to speed with what’s been going on in the meantime. But it works, though, because the characters are interesting, and watching them both progress and regress as time goes by is legit interesting.

Martin Eden

I’m not a Jack London guy; never read any of the books, not really sure what his place in the wider popular culture is (the closest I got was that one episode of Next Generation where Data goes back in time, and there’s a Jack London cameo. It was a pretty crap episode). But I still liked this a lot, with my lack of Jack London know-how not serving as a detriment to the movie at all (I had to resort to Wikipedia for trivia, and I was informed that this is apparently only “loosely based on the 1909 novel of the same name”). It’s immersive as hell, with some vibrant cinematography, really smart editing choices, and a central performance that a) was great, and b) kept reminding me of Christian Bale, what with his chin and his intense stare. There were a lot of behind-the-scenes choices made here that I think benefited the overall film greatly, like how they never really specify exactly when this movie is taking place (I saw one online outlet liken this tactic to what Transit did with its nebulous setting, and I think that’s appropriate). I also like how basically the whole movie we’re left on our own to decide how we feel about anything that’s going on. Specifically, I’m thinking of Martin’s politics (it can occasionally be annoying when a film doesn’t take an overtly hardline stance on these kind of issues, but here I think it was appropriate), and his romance.

The love between Martin and Elena is one of the film’s smarter flourishes, because at every turn, we’re invited to wonder whether or not they actually work as a couple. He’s clearly not welcome in her world (at one point, he goes to a classy party, and there’s a clever, Silence of the Lambs-style shot where he’s the only one not wearing a beige suit), and he doesn’t want to be, anyway. He writes passionately about harsh poverty and destitution, subjects that Elena wishes to simply avoid. But he’s also a forceful dick, someone who hinted early on that he was eventually gonna grow into an absolute self-righteous shitheel. That said, this isn’t like…I don’t know, Valerian or something, where you’re genuinely left scratching your head as to why either of these people can even stand to be in the same room as each other. Martin and Elena have legit chemistry, and the film does good work at visually suggesting their connection. Remember up top when I said this movie had smart editing? When I wrote that, I was specifically thinking of this sequence early on where we cut between Martin on a boardwalk, strolling beside the raging blue ocean, and Elena playing the piano, the camera really capturing the vibrant blues of her eyes. Blue is a constant color throughout this movie; come to think of it, I haven’t seen overt color-coding like this since Manhunter. Good shit

Shirley

In case my entry for Ordinary Love didn’t make clear, I have absolutely no time for traditional Oscarbait biopics, the “based on a true story” nonsense that seems tailor made to give Academy voters a hard on. If it were up to me, all biopics would take the track that Shirley does; instead of trying to present an “accurate” view of what she was “really” like (which is an impossible task, destined to fail), the film instead cleverly repositions itself as more of a “spiritual” representation. It’s the life of Shirley Jackson, as seen through the lens of a Shirley Jackson story. That’s right, instead of another weepy, serious bit of Oscarbait nonsense, we’ve got a legit gothic horror movie on our hands, and what’s more, it’s a real good one. Not since Capote has a biopic of a famous author delved so effectively into what their work was actually like.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

Much like The Assistant, this is another movie that could’ve felt low-key to a fault, but somehow it stays on just the right side of its minimalist style so that it never feels boring. What’s funny is, I keep having to remind myself that this is technically a “hot button movie,” since it deals directly and frankly with abortion, but the movie’s lived-in naturalism keeps the focus where it belongs; on the characters in the story, and their journey. What could’ve felt almost punishingly down-to-earth is given a real minimalist power

Saint Maud

I had a feeling when I first watched the trailer for this…god, it must’ve been over a year ago at this point? Anyway, I got a strong impression from watching that that this would be a movie I’d vibe with. The trailer was giving off the right kind of energy, and while that is by no means a guarantee of success (as anyone who remembers 2020’s The Grudge can attest, it’s much easier to make a good horror trailer than it is to make a good horror movie), I did notice that this was a movie coming from A24, who have a pretty good track record in this area (their previous religious horror movies: The VVitch and First Reformed. That’s fucking pedigree right there).

Anyway, I am sooooo glad I waited before making this list so that I could see this, because my instinct was right; the list wouldn’t have been complete without it. This is a fantastic thriller, one of those brilliant “how much of this is real, and how much of what we’re seeing is just the main character going insane?” horror movies that thrives on uncertainty.

The Invisible Man

If Saint Maud was the properly scary horror movie of 2020, this here is the fun horror movie of 2020. Which works, since the main boon for classic universal monsters was never that they were scary; oh, they were atmospheric, sure, but none of them were particularly frightening. Rather, they were fun, and iconic, and a bit camp, and that’s I think what Leigh Whannell was smart enough to lock in on for his remake, easily the best horror remake in quite some time. Not since Jordan Voight-Roberts has a filmmaker managed to make a studio film that felt this personal and scrappy. The Invisible Man’s success must be something of an embarrassment to Hollywood; they were all set up with their big extended universe to match Marvel, only for that whole thing to crash and burn one movie in. And then, to add insult to injury, The Invisible Man came along, kicking its big-budget predecessor’s asses so hard, and with such superior filmmaking, that now the Tom Cruise Mummy is somehow even more of an irrelevancy than it already was. I didn’t even think that was possible!

Saint Frances

Here we have a movie, like Never Rarely Sometimes Always, which is technically a “hot button movie” – in that its plot includes topics such as abortion – but when you actually sit down and watch the thing, all that stuff flies out of your head and you’re left with this empathic, soulful character study. This is a rough one to describe, because no matter what way I attack the story, it’s going to end up feeling rough and disjointed, tackling too many things without any coherence or clarity. The strength of Kelly O’Sullivan’s script and Alex Thompson’s direction (their first forays into both departments, amazingly) is how well they manage to encompass all these disparate themes and events as if they were all connected by one narrative thread. It’s a movie that contains multitudes; it’s wrong to call it a comedy, despite it being occasionally very funny, and it’s wrong to call it somber, despite it being frequently melancholic. It’s a lot of things, and they all compliment each other.

The Gentlemen

The Gentlemen isn’t the “deepest” movie of 2020, and it wasn’t the most “meaningful” or “impactful” or whatever other words you want to use. But in a very real way, this might’ve been the most valuable. There’s a reason that, for all the movies I saw in the cinema early in the year, this is the one I kept coming back to months into lockdown. It’s just fun; better, it has enough sense about itself to know when to push the joke, and when to lay off. There’s a sense of tonal control here that speaks to real skill behind the camera, and I say that as someone who hasn’t always been impressed with Guy Ritchie’s output.

Speaking of, this is the movie Ritchie made right after his horrible Aladdin live-action “movie,” and I gotta say, there is such a tangible difference between this movie – which he was clearly passionate about – and that movie, which just screams “paycheck job.” Which, honestly, more power to him; this is probably the best case scenario for directors working on those big, stupid Disney properties. Make the hack job, rake in the dough, and then use that money to make something that’s actually worthwhile.