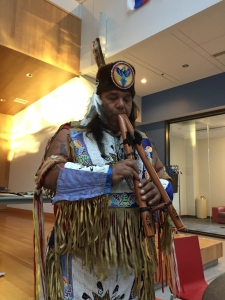

On November 16th and 17th, Goucher welcomed world-renown indigenous songwriter, Jody Gaskin. Adam Geller, ’18, who is known for his flute playing and drum circles on campus, applied for a social justice grant a couple of weeks before the event. Having gotten to know Gaskin by traveling the Powwow trail selling tea, he knew that he would be the perfect guest artist to familiarize Goucher students with native music and history.

On the night of the 16th, Gaskin performed a Native American rock concert in Merrick. He began with some storytelling followed by a couple of songs about his tribe and native history, and ended the evening with a hoop dance, using hoops to make shapes representing different animals. “I’ve been singin’ on a drum since I was in diapers,” he said in an informal interview, “and I’ve been dancing since I could walk.” Inspired by his mom, who was a “big rocker” and listened to a lot of Motown, Gaskin began playing the guitar at 14 and began writing songs off-the-batt. At 15, his mom bought him his first, acoustic guitar. Today, Gaskin has won numerous awards for his work as well as performed to a variety of audiences around the world.

For Gaskin, songwriting is about “telling a story, not just meaningless stories.” He explained that social justice songs were big in the 80’s but not so much today. On the 17th, during his roundtable discussion, he demonstrated just what good storytelling was about. “1,000 to 15,000 years, ago, a young boy was given a vision to leave,” he began. He recounted the origin story of his people, the Ojibway (often misnamed the Chippewa), explaining how their migration throughout the continent was at first shaped by the foresight of a boy given a prophecy by megis shells rising out of the water. The boy warned his people of a threat coming from the East and spoke of “a place where food grows on the water”: the Apostle Islands of Lake Superior, where wild-rice grew in abundance. This area eventually became the capital of the Ojibway nation. Gaskin then interwove the origin story with a historical overview of Indian-White relations, explaining how colonists like Samuel D. Champlain “sent soldiers [to the Great Lakes region] to break s**t.” In 1763, a group of frontiersmen in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the Paxton Boys, shot Indians on-sight and hacked them to death in what became known as the Conestoga Massacre. “There’s a historic trauma that comes with that,” Gaskin said.

Native Americans’ feelings of anger and frustration are exacerbated by the fact that the US government continues to pose a threat to their existence and ways of life. “Life in the res sucked, sucked, still to this day!” Gaskin said. “They’ve got a bottomless bag of dope and a bottomless bag of booze.” Despite numerous instances of benevolence on the part of native peoples towards whites, their contributions to the US via military service, economic participation, etc., and a number of treaties signed with the US government, natives to this day must fight for basic rights. The events at Standing Rock are just one example. While officially recognized native groups retain reservation rights, mineral rights must be bought separately. Any oil or mineral company can drill beneath their lands unless they purchase those rights. What’s more, the US government has driven deep divides between groups through an uneven allocation of funds according to blood-ties. While some nations, like the Seminoles (who own every Hard Rock Cafe around the world) have been incredibly successful, others are struggling to make ends meet.

Gaskin’s event took place shortly before Thanksgiving, a holiday that tends to perpetuate a false narrative of Indian-White relations. His performance on the 16th, followed by his roundtable discussion on the 17th were a reminder that, while spending time with family is important, it is equally important maintain awareness about the persisting discrimination towards the Native American peoples. Just as easily as a story can be told, a story can be unwritten.